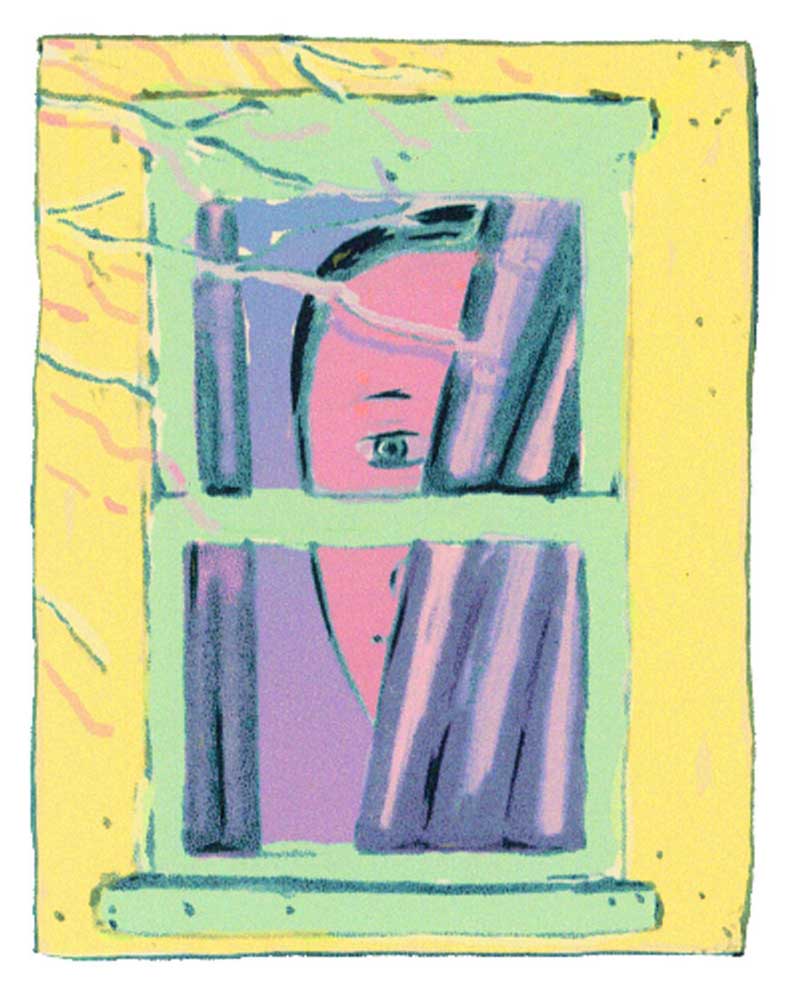

"A Room with a View"

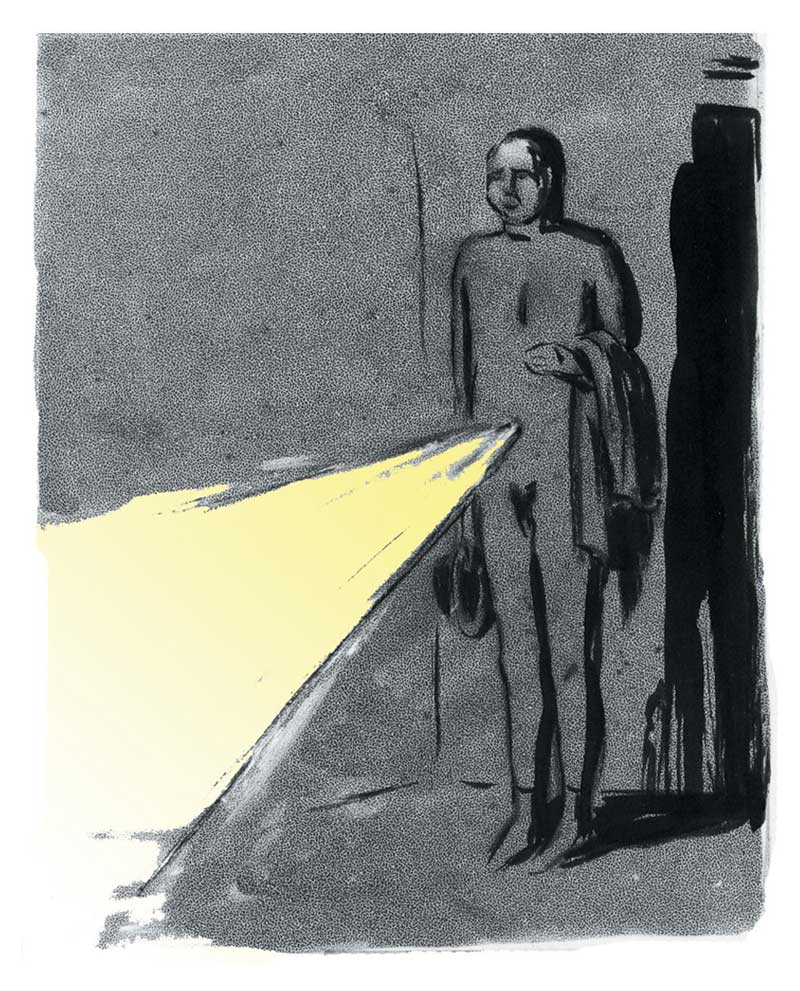

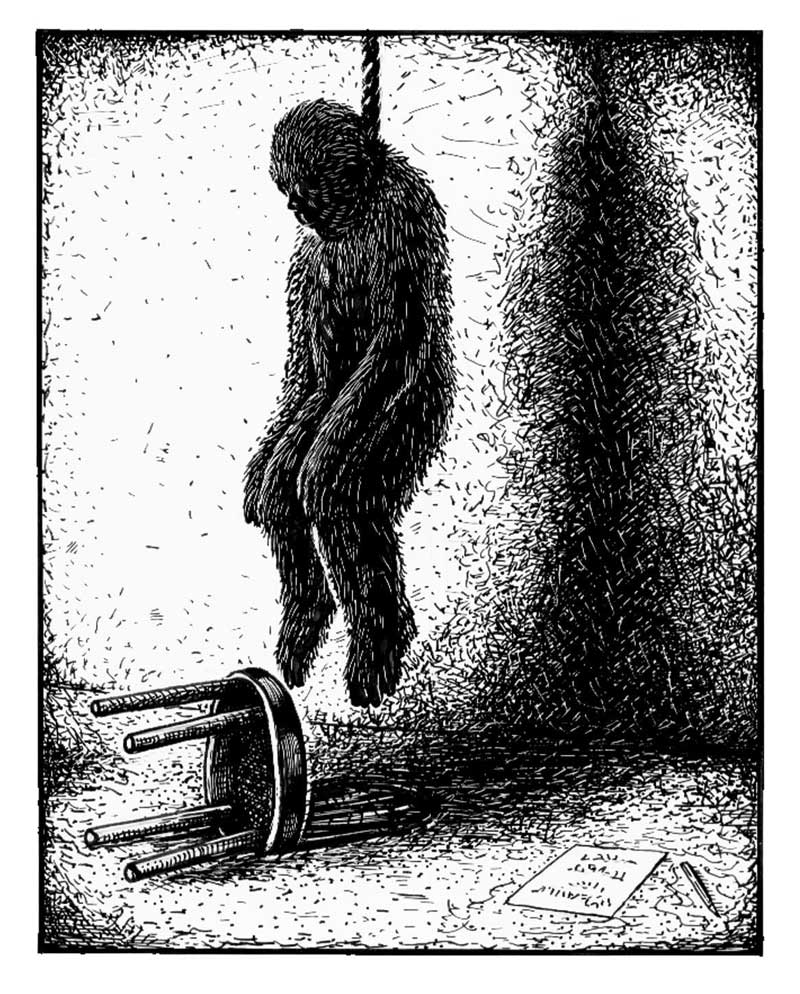

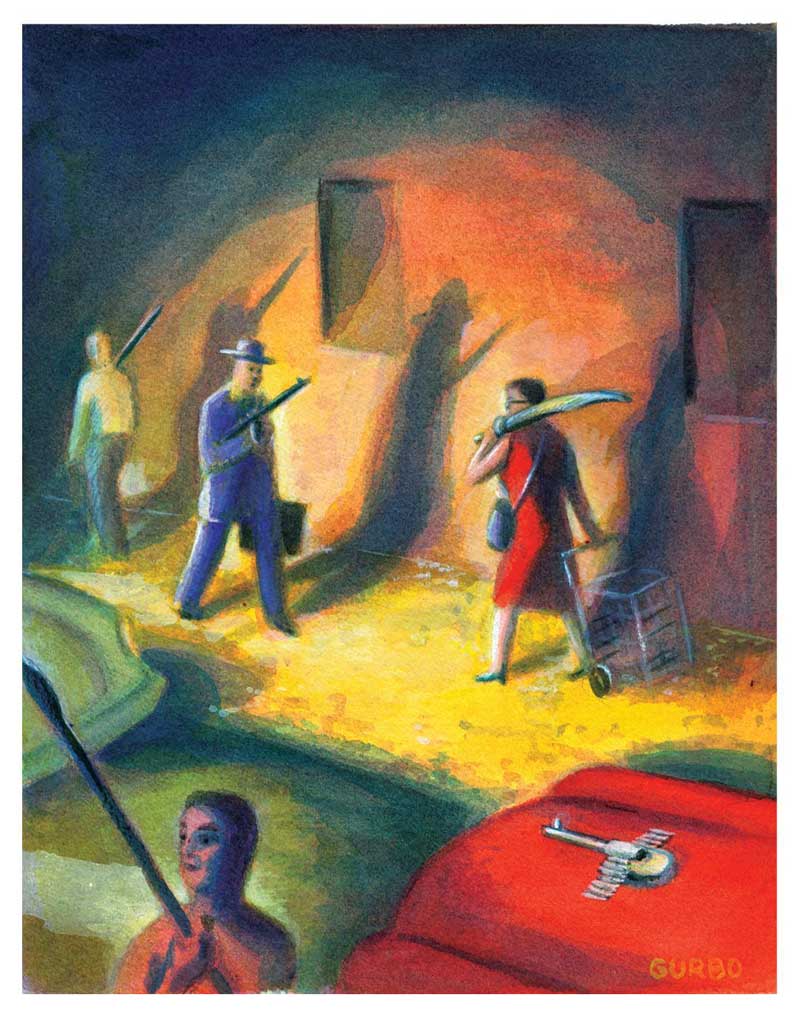

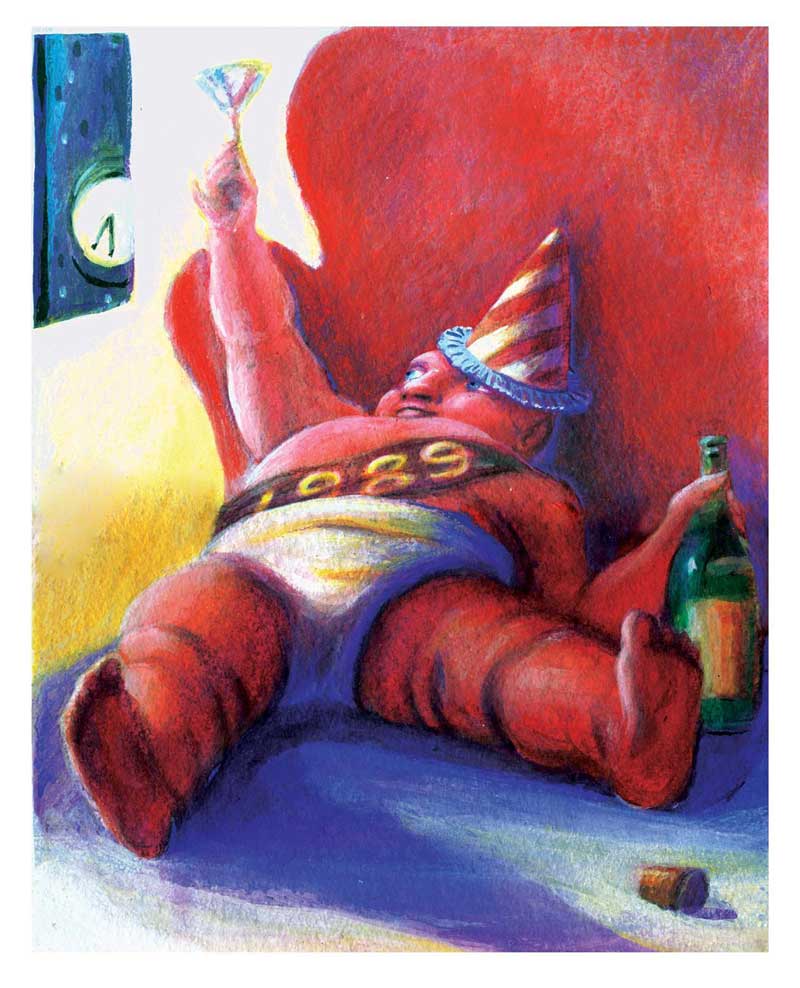

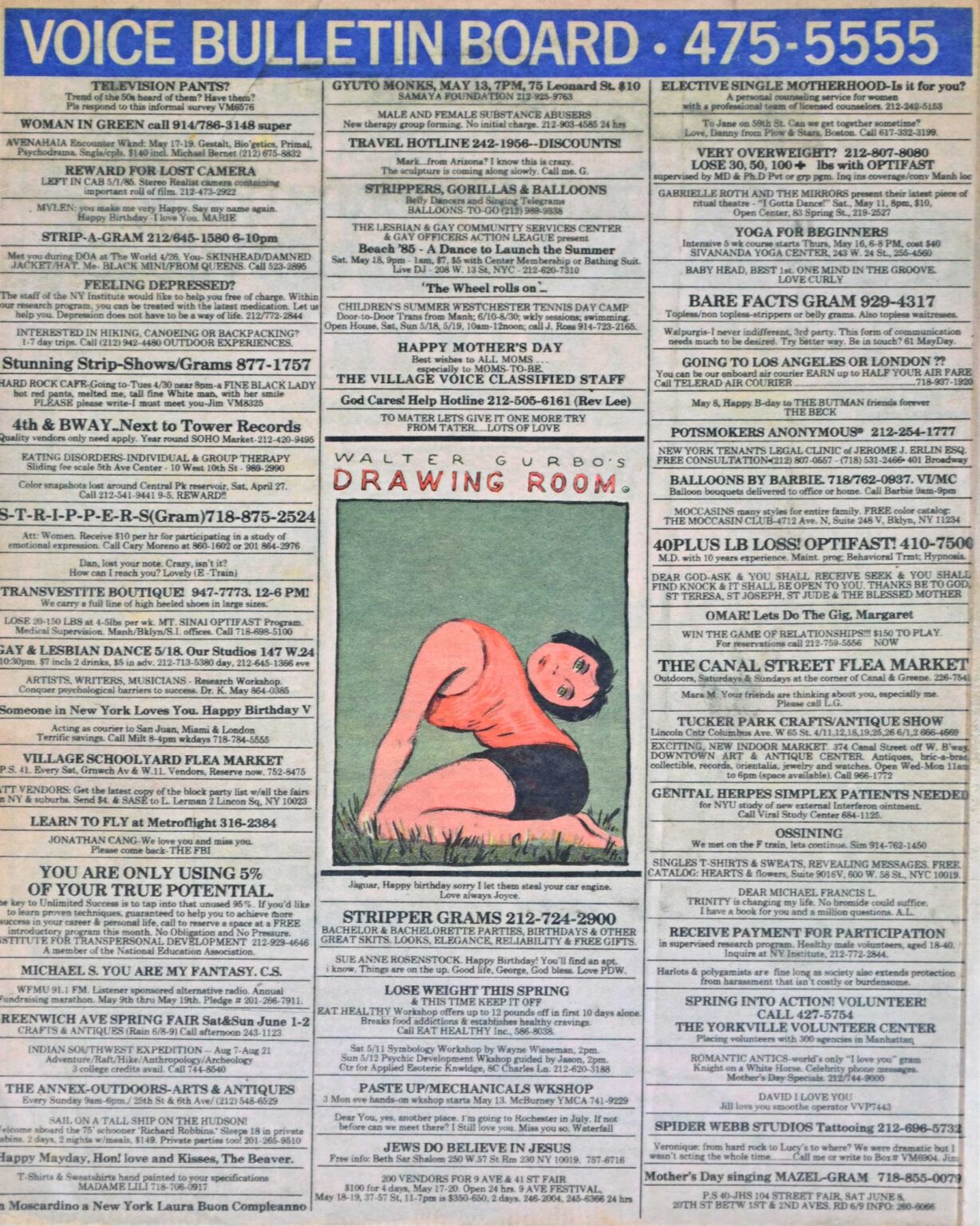

For over a dozen years, from 1977 to 1989, on the back pages of downtown New York’s former preeminent local crier, The (Village) Voice, was a picture window. An oddity by most any standards today- already then more an atavistic throwback to the underground press of yore- its curious fit within t he low-end commercialized zone of this once radical weekly seemed with each passing year ever-more like some out of time eccentricity, a past whimsy that by the grace of its wit somehow continued to survive on amidst pop culture’s pernicious progress. Thinking back on it now, Walter Gurbo’s Drawing Room was not just a weird hole punched into the wall of babble, but something of lost strand connecting the impoverished means and grand illusions of New York City at its late Seventies economic nadir and creative apogee to the rising bottom lines. Escalating costs and rising expectations that have only grown exponentially since then.

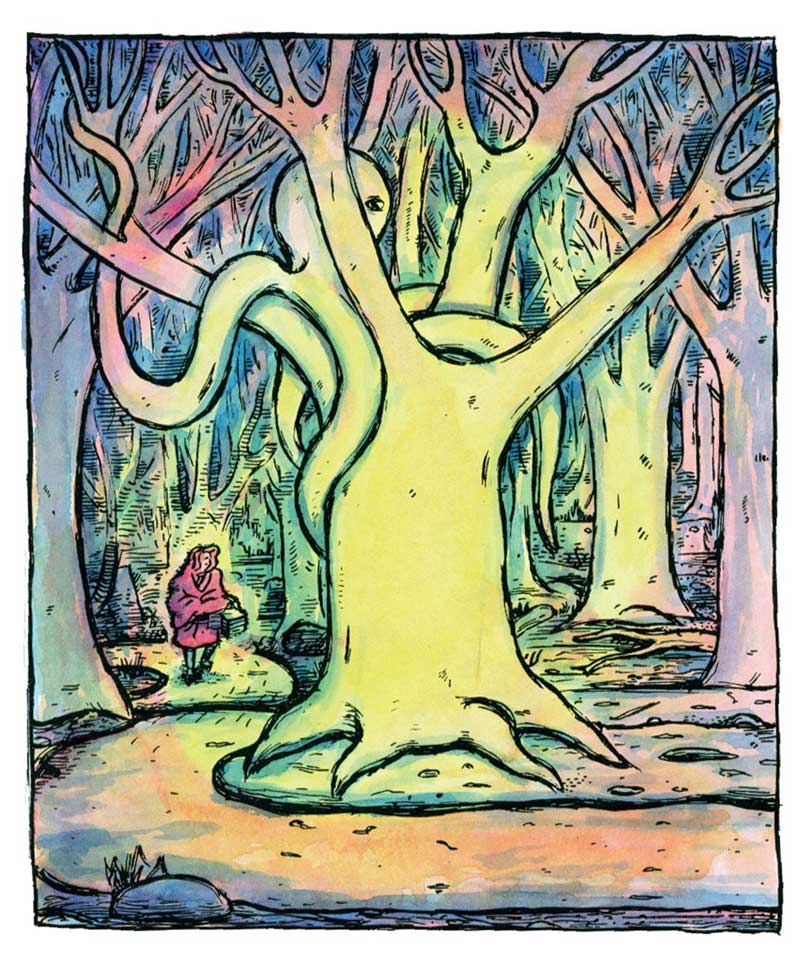

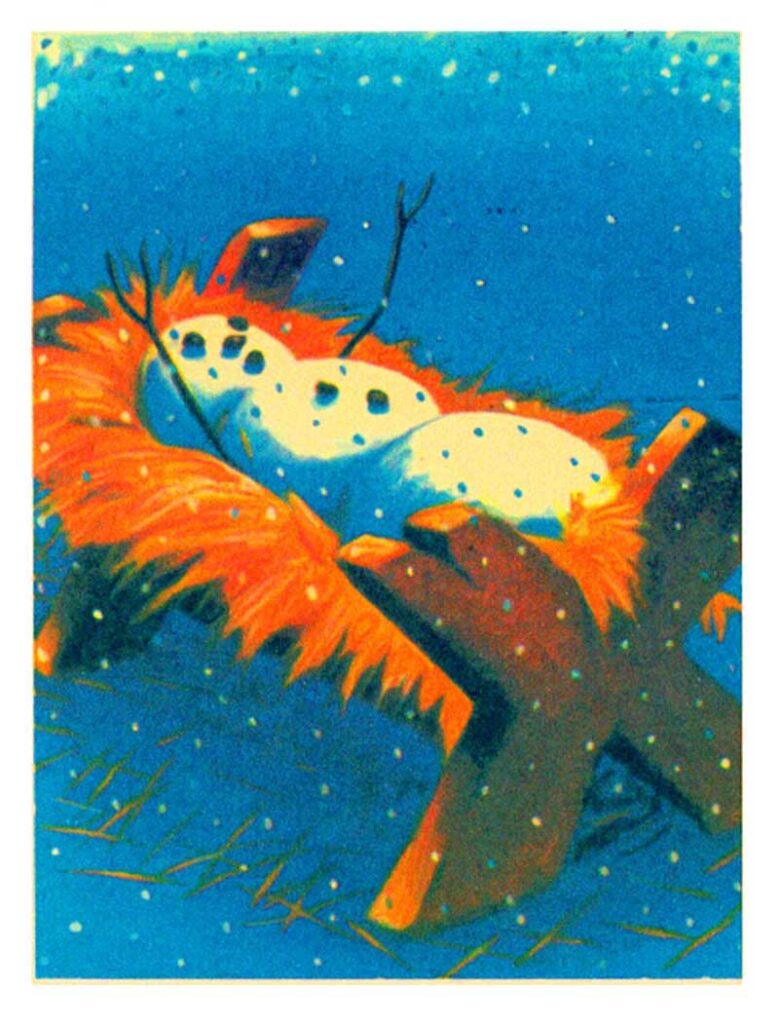

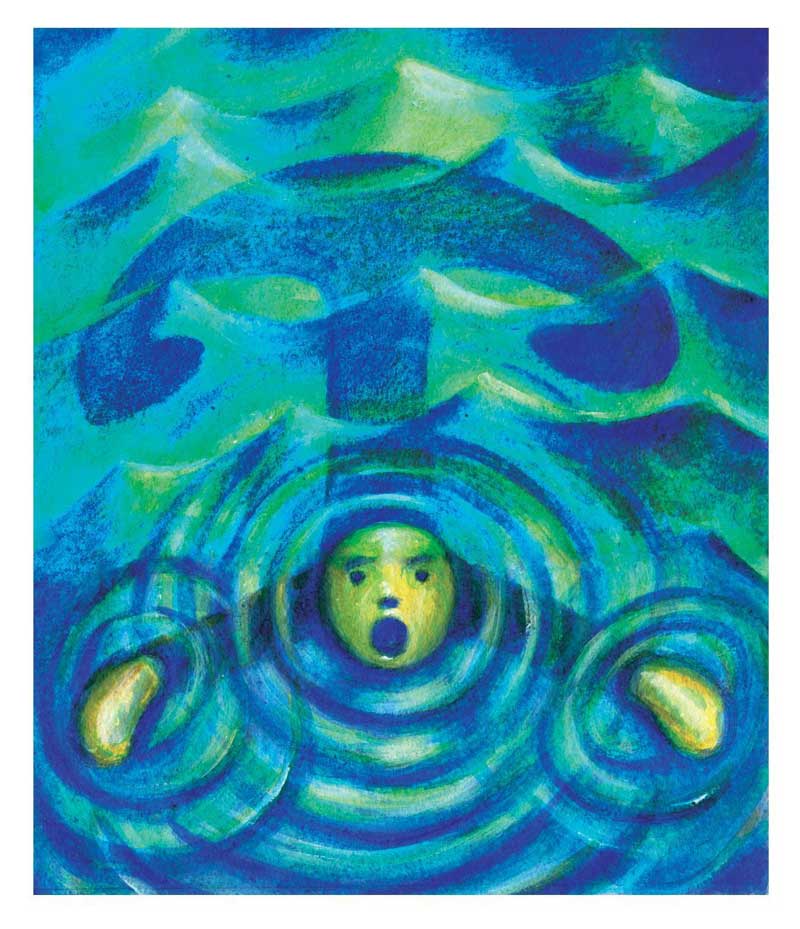

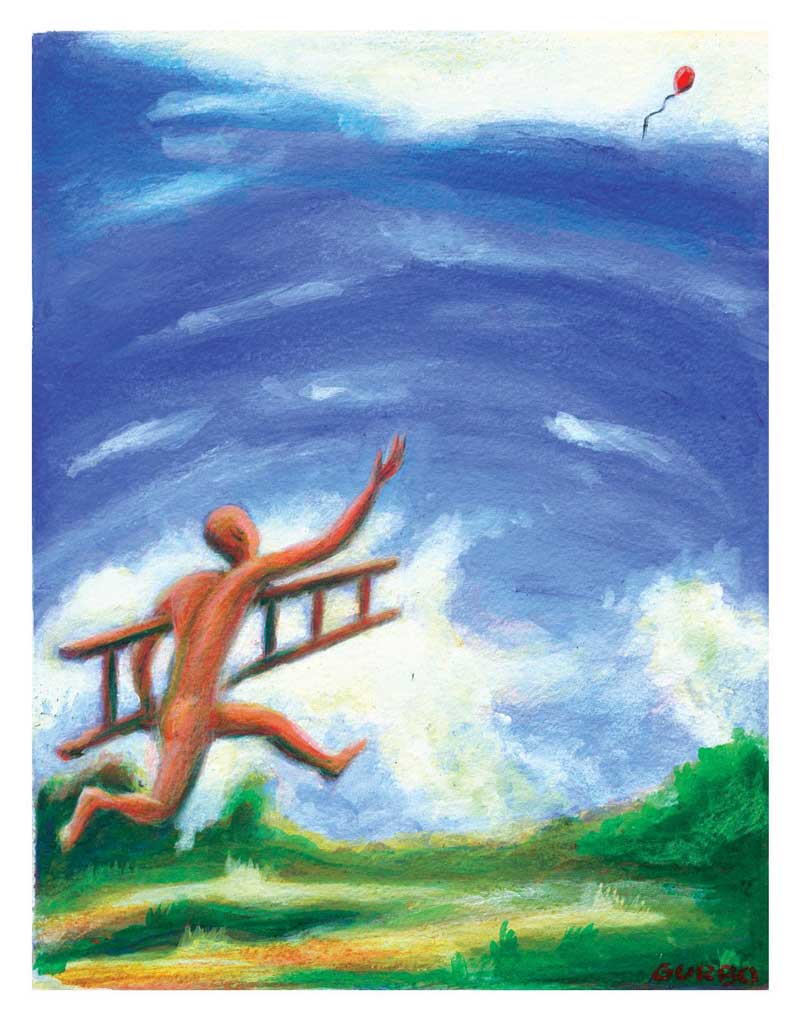

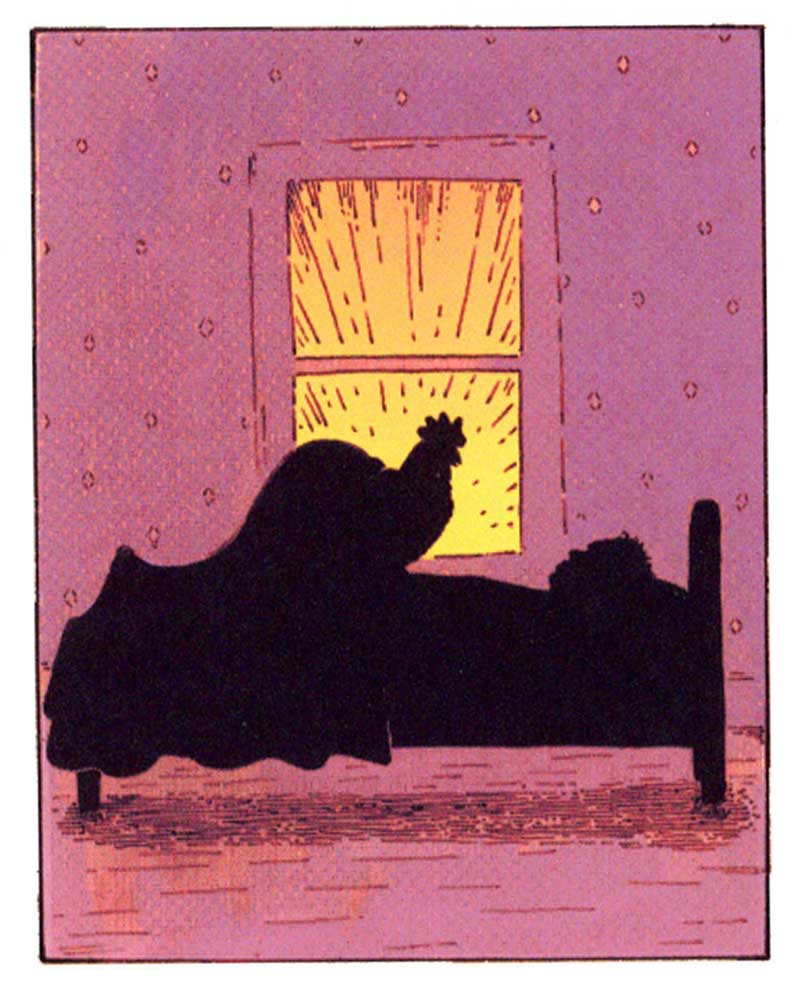

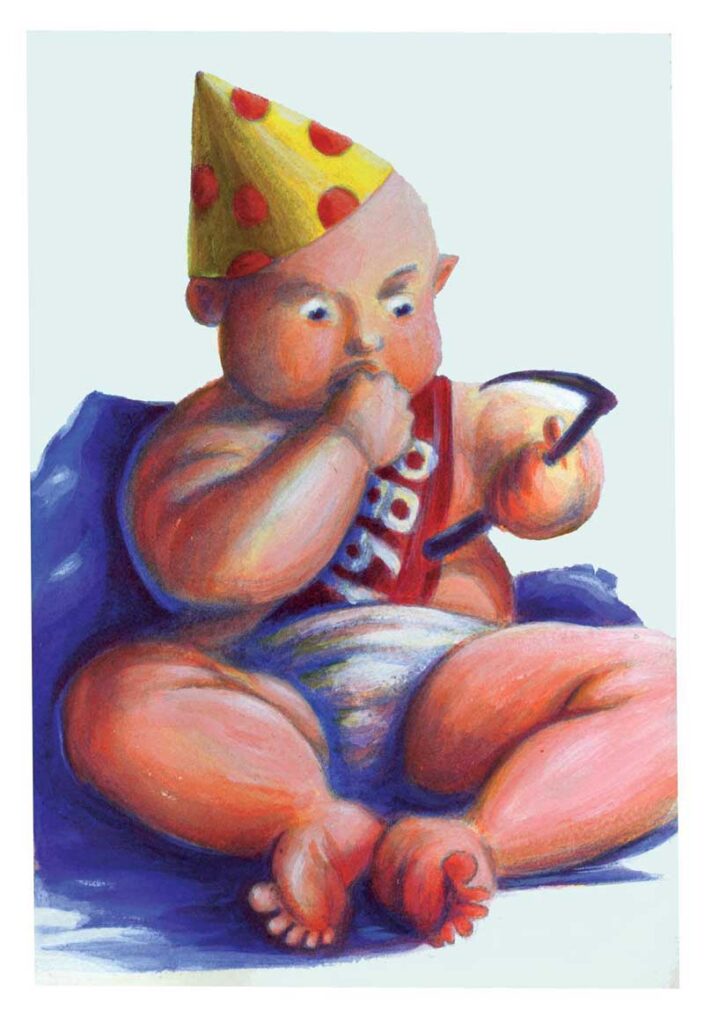

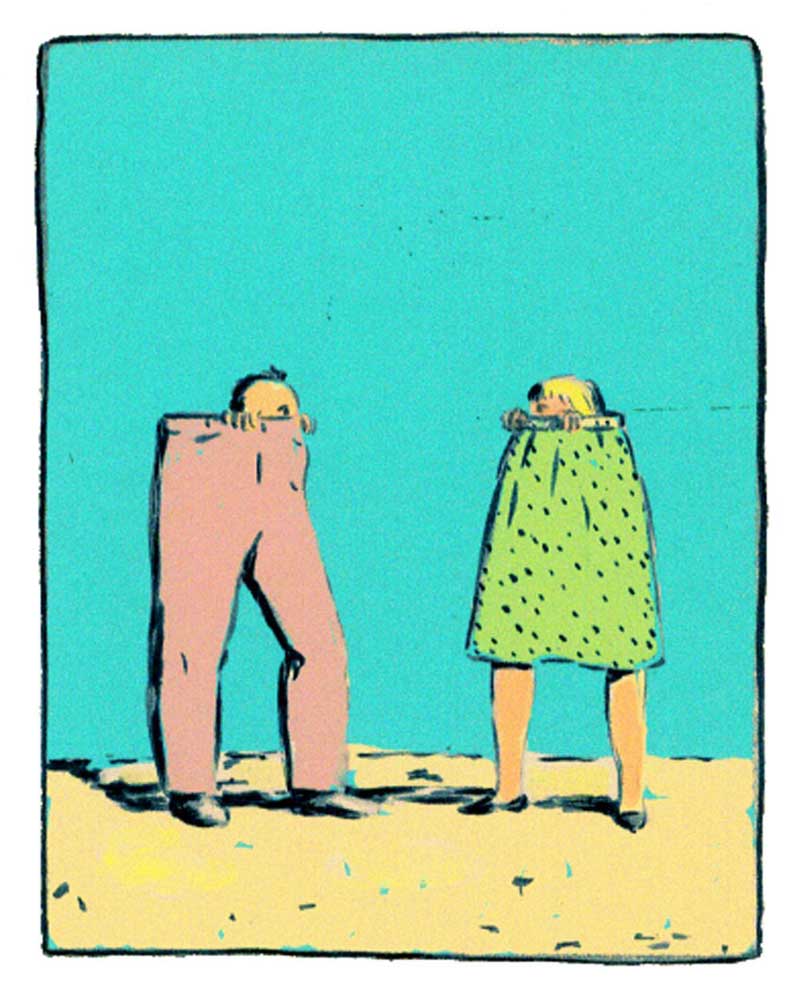

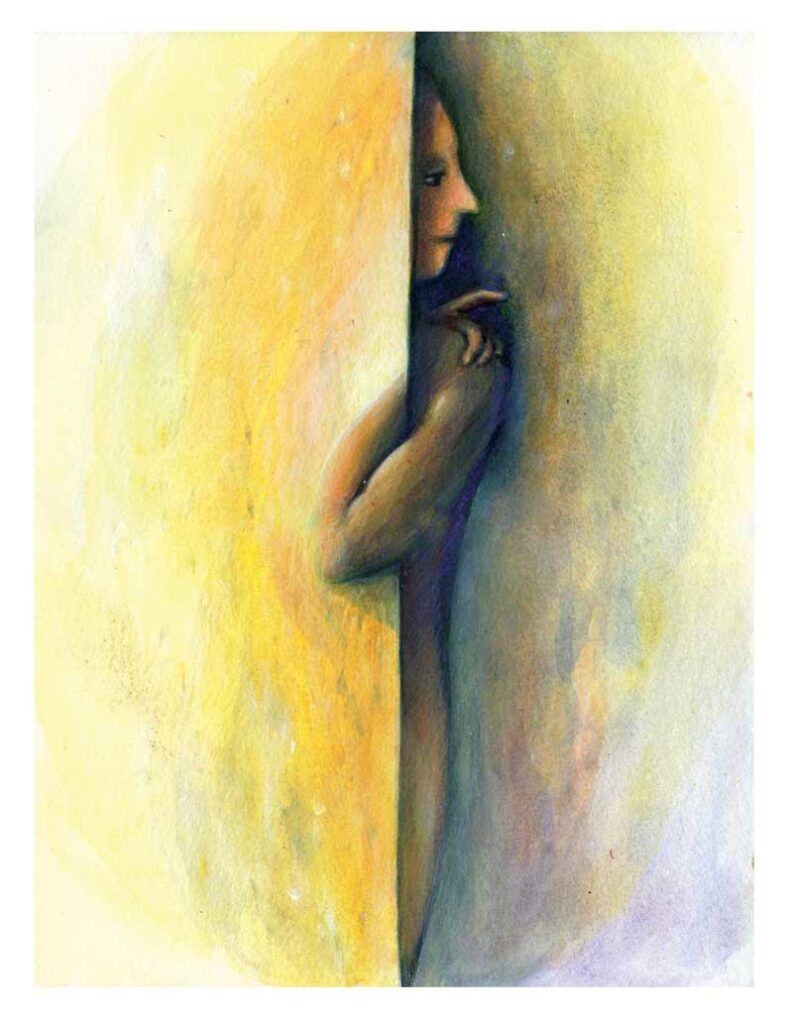

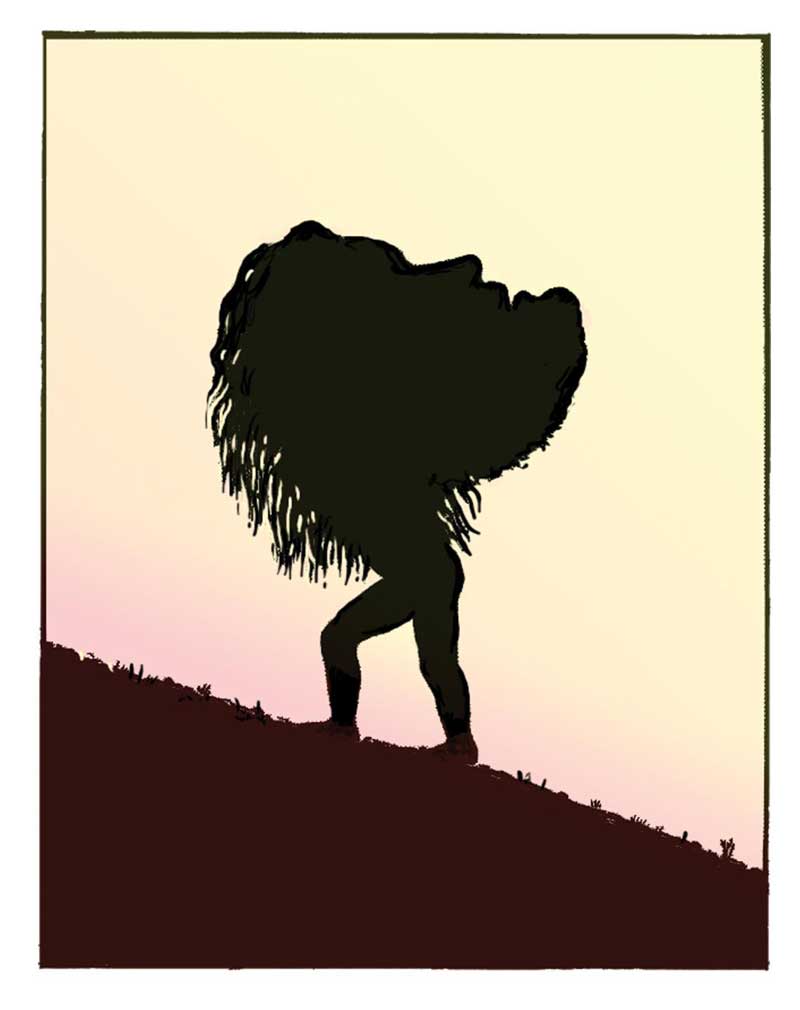

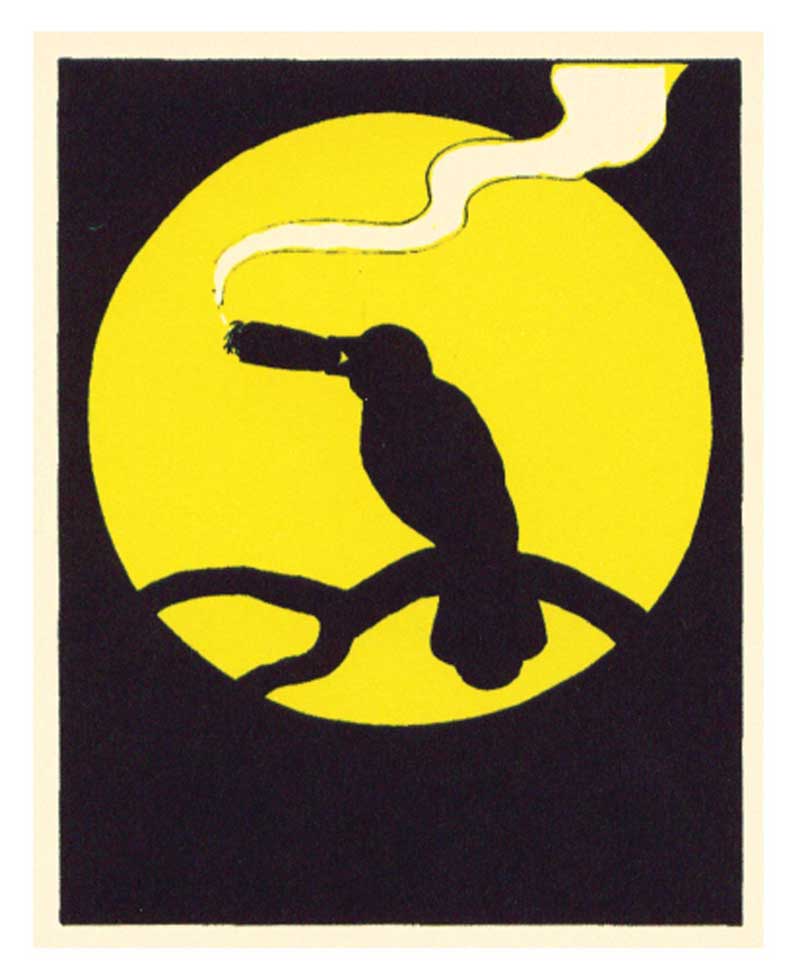

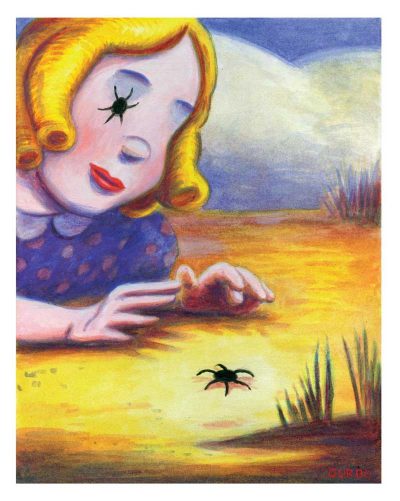

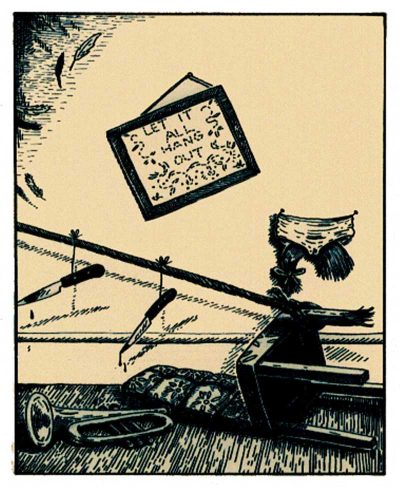

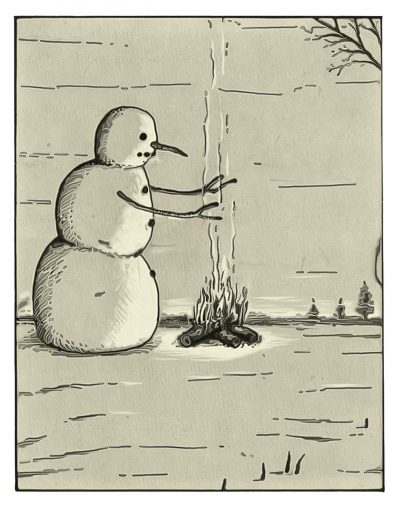

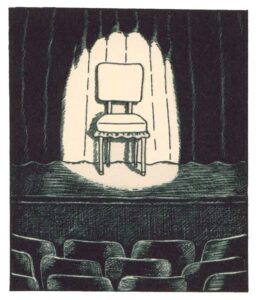

So playful, theSe drawings never grew up, got tired or sold out. Nothing can surprise New Yorkers it’s true, but that’s a good part of why they make a perfect audience for the absurdities that made the Drawing Room such a comfortably familiar fixture among all the other cropped views and mini-dramas glimpsed like prurient snatches in the tenements, towering offices, migratory street corner socials and (of course) subways of Gotham. In a maze of walls, canyons that make anything above gutter level seem like big sky country and a compartmentalized nexus of endless boxes, you get used to looking through windows. I’m not sure we could have ever really understood or collectively shared Gurbo’s vision if it were not inherently blinkered. It’s not a picture unless it has a frame, and it’s not a view unless that frame is a window.

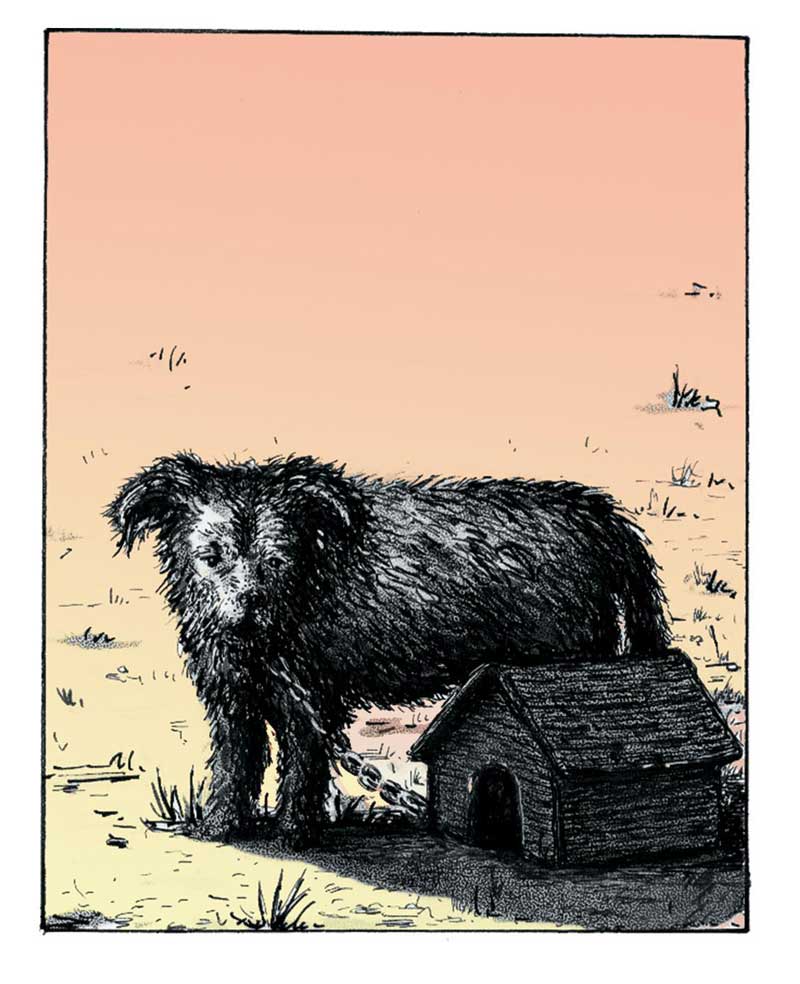

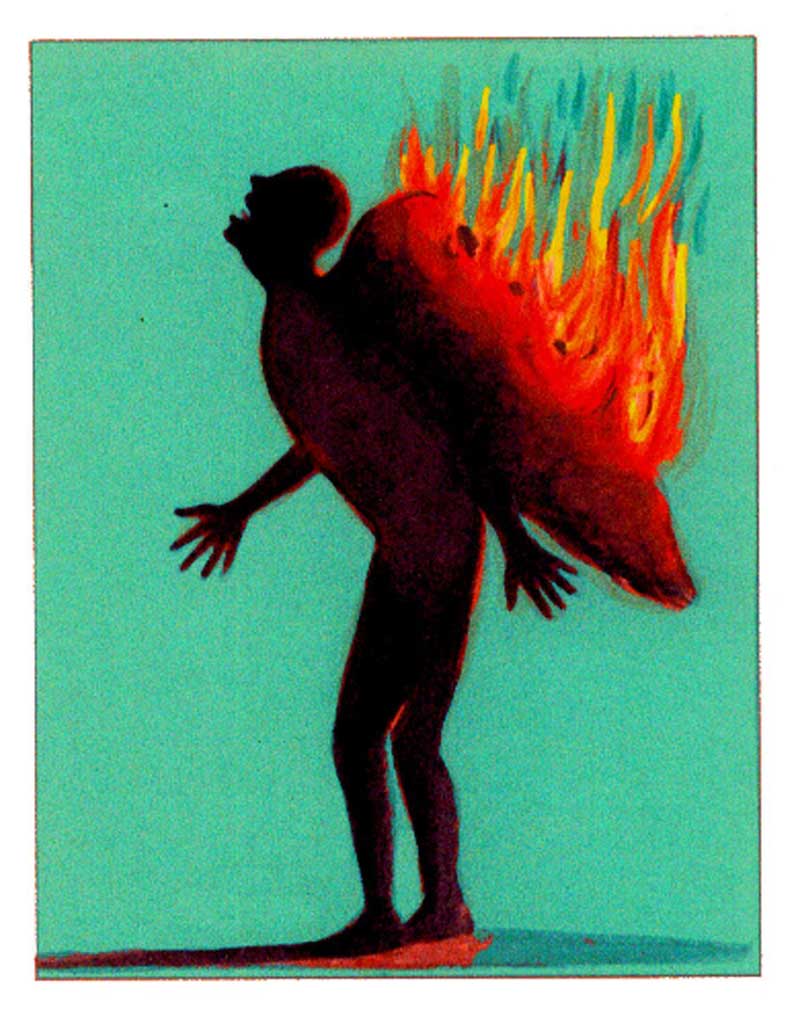

More than thirty years since they were first dreamt the drawings remain here, hut the room is gone. That sort of space can hardly exist when neither the premium of real estate in the media nor the city can afford such follies. Also lost is this peculiar kind of disjointed view, now all but obliterated by the new tide of luxury high rises. But to remind ourselves that we are still a tribe of urban eavesdroppers, it’s only when you listen rather than look at these pictures- perhaps hard to do as they remained staunchly wordless in their slapstick pantomimed anarchy- that the artist’s voice sounds oddly familiar. Yes, this is the absurdity of the overheard, the accidental and random that yet echoes with all the feverish distortion of an ever-looping feedback. And to hear it here you have to remember what could be said before computers and their proliferate effects, in companionship with art directors, photo editors and ad-marketing-sales departments, wiped out illustrations, cartoons and comics off the pages and into the margins.

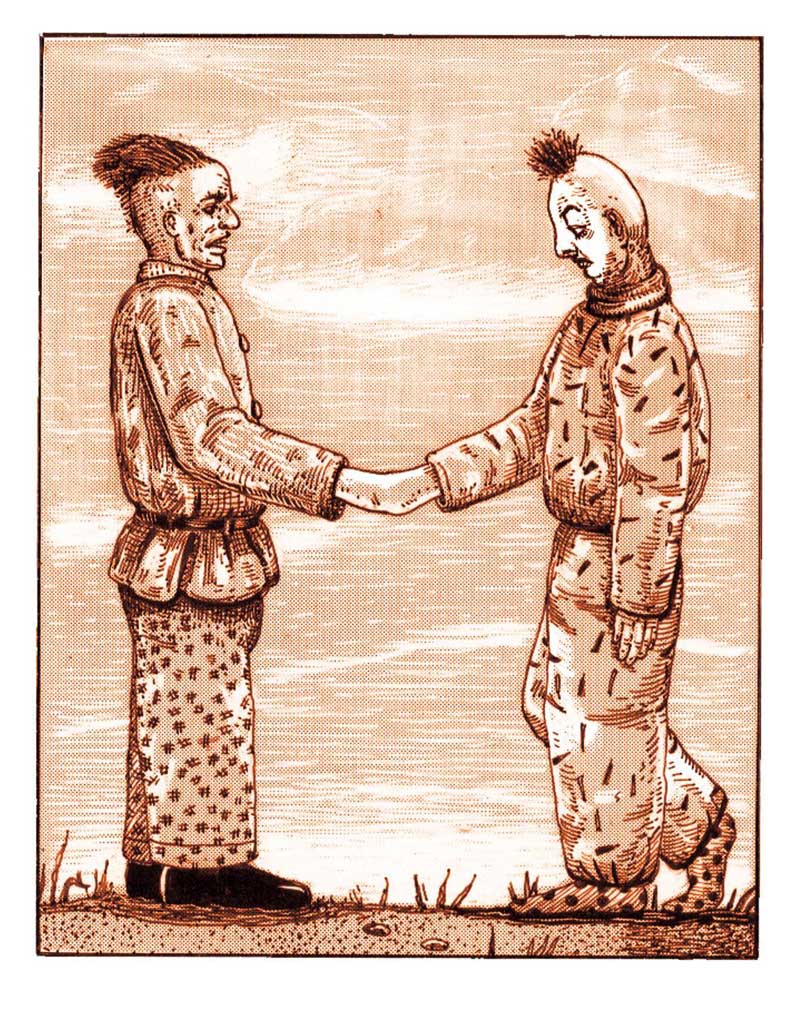

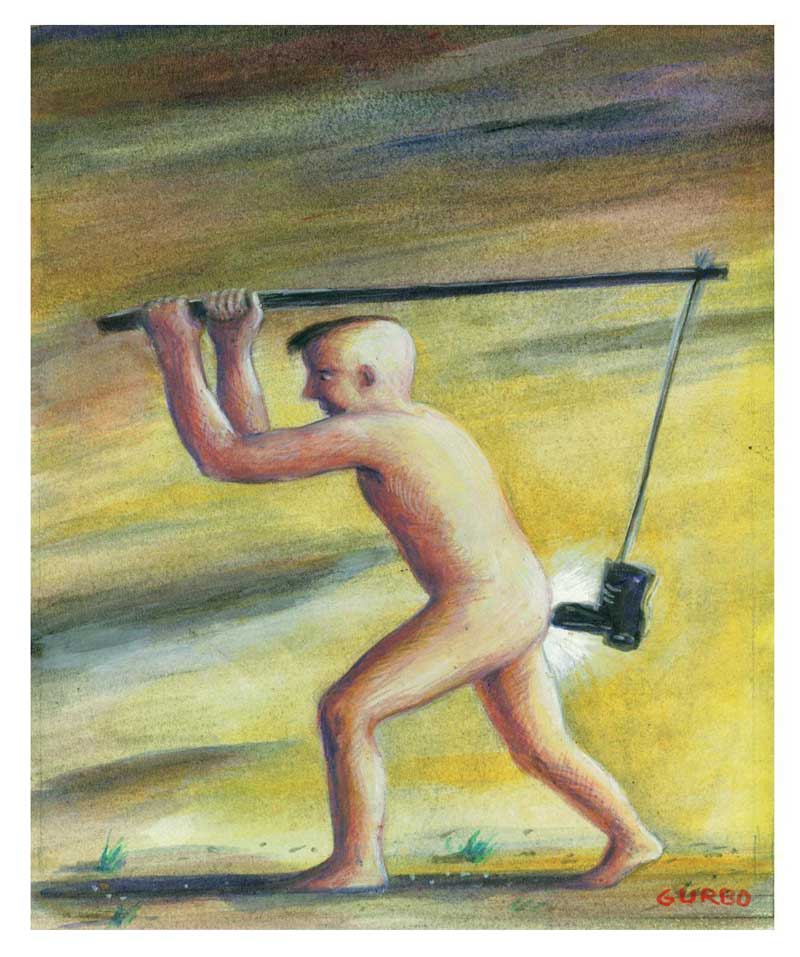

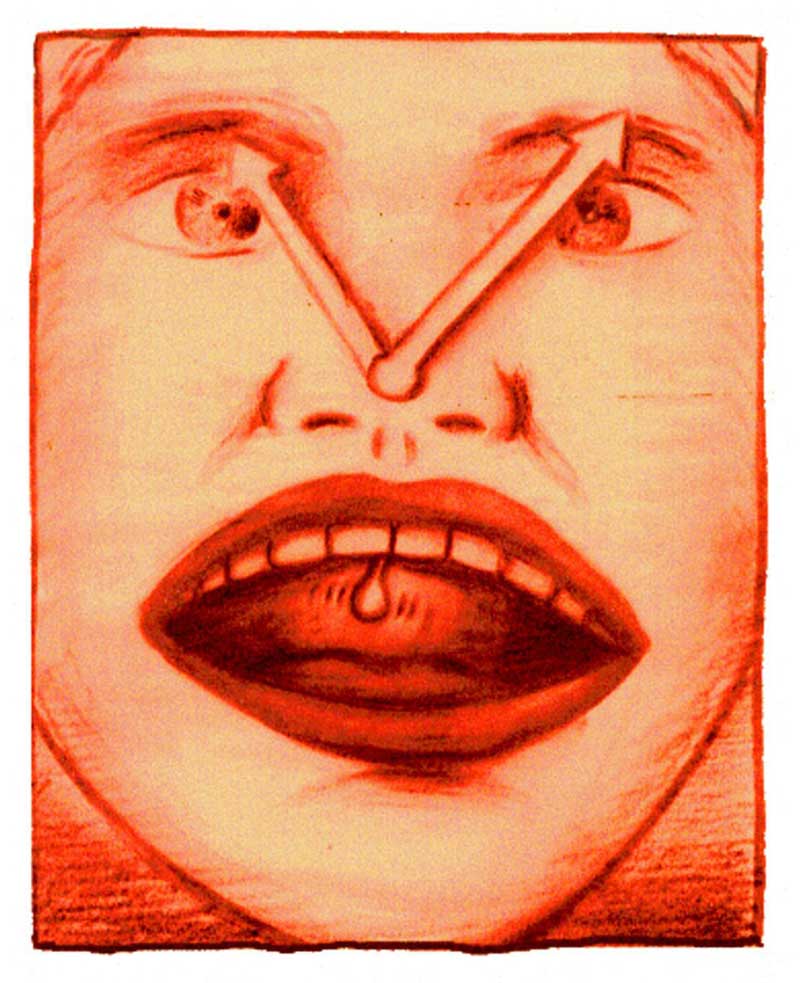

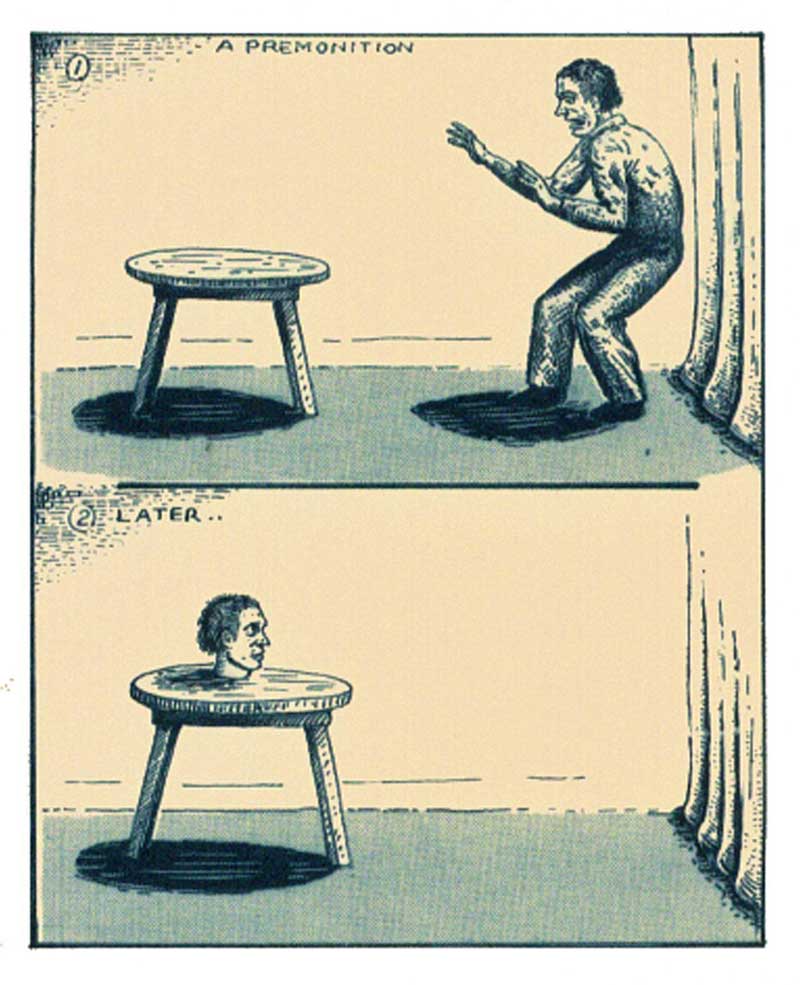

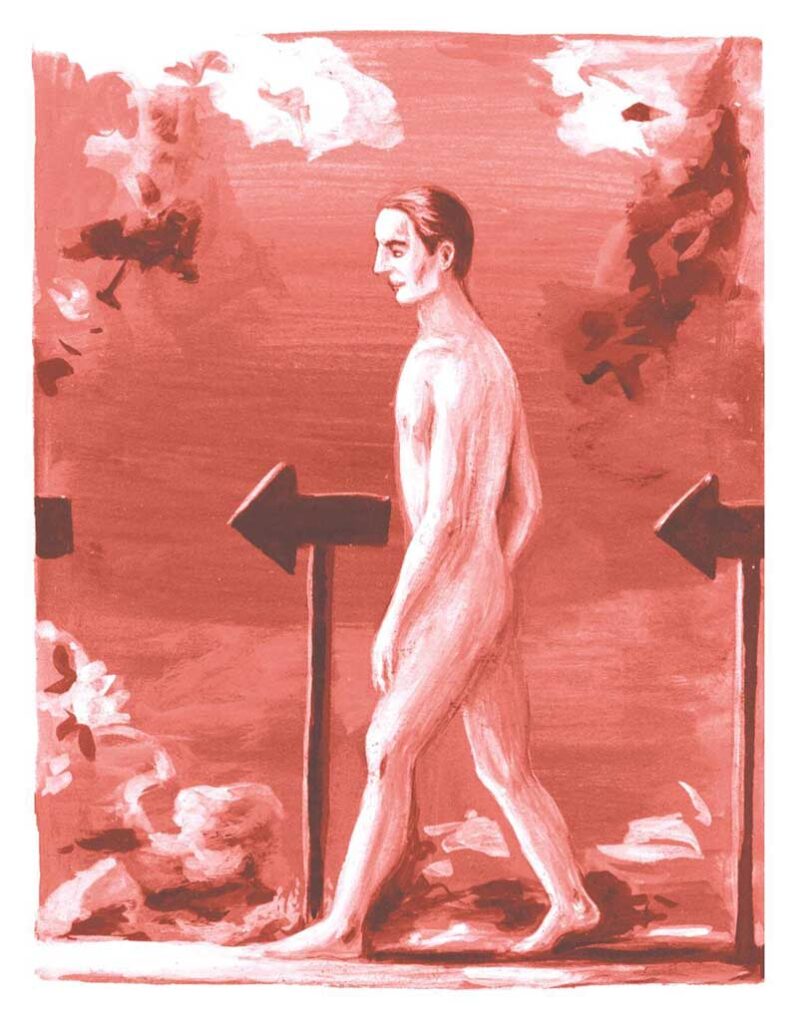

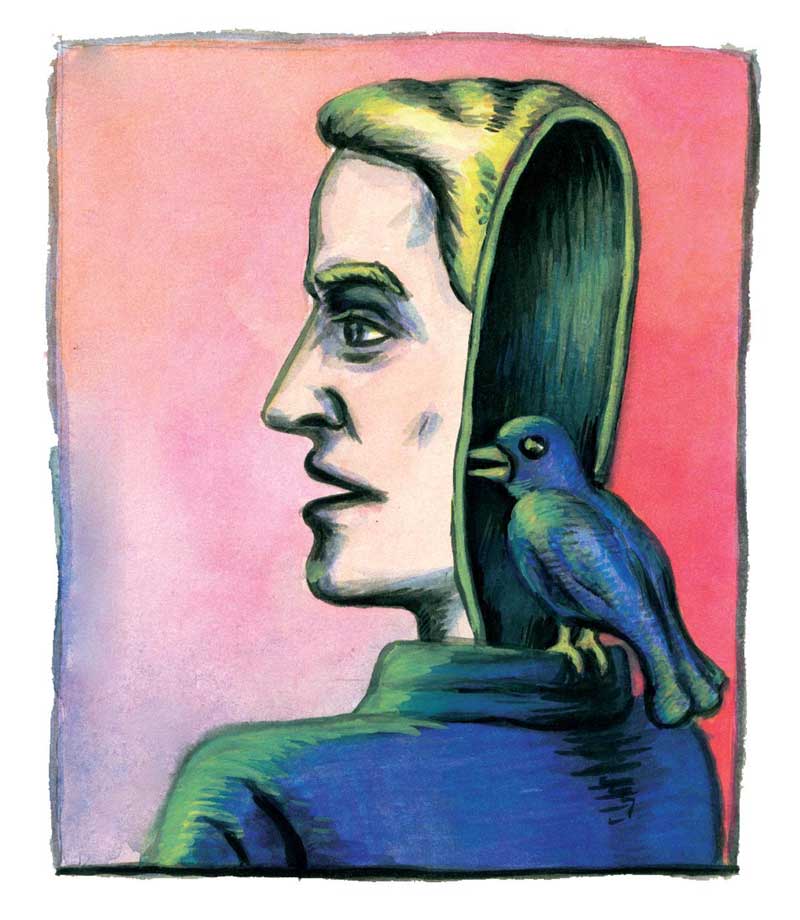

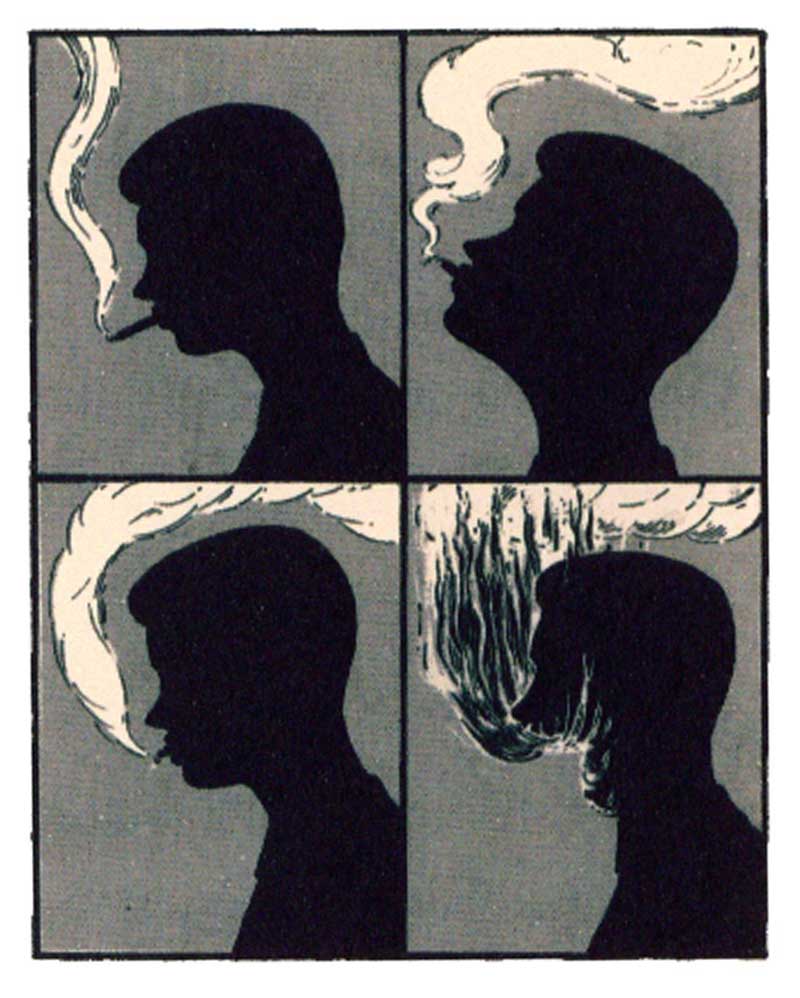

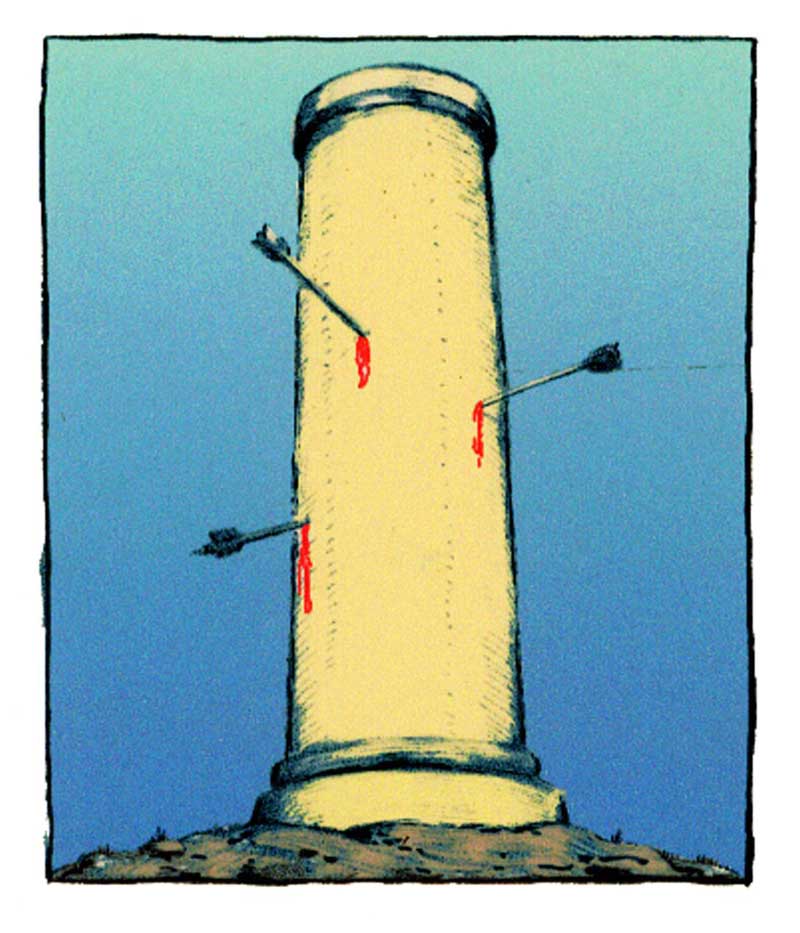

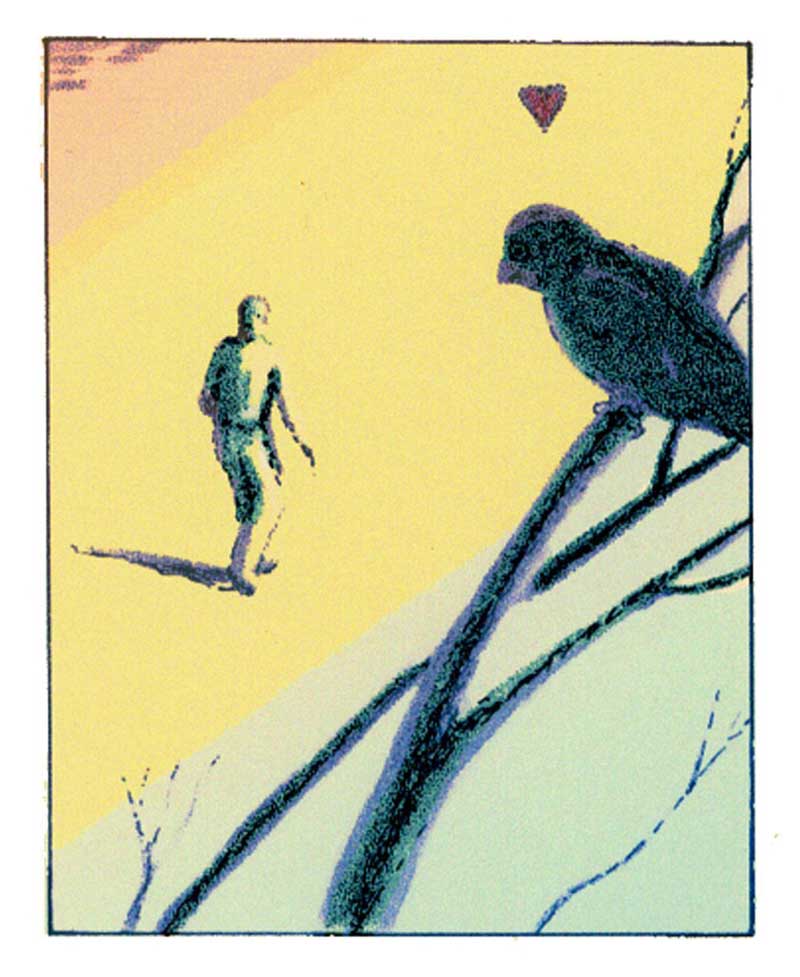

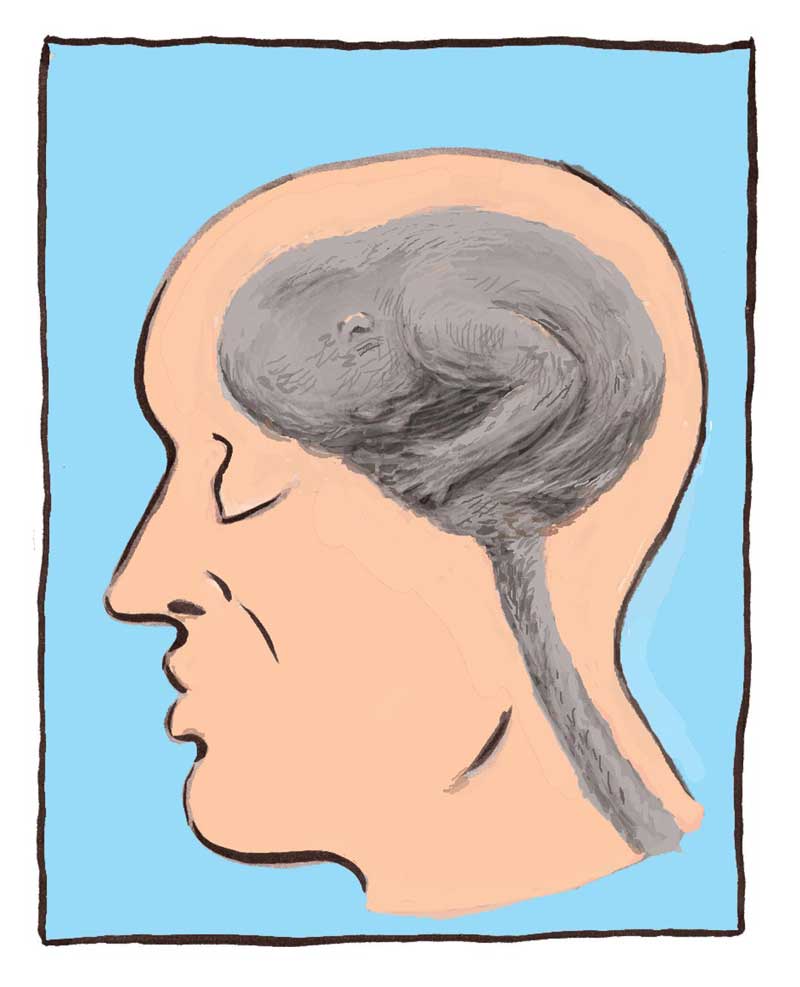

Walter Gurbo belongs to a longer lineage of American vernacular, with the same bizarre twists and acerbic distortions forged by Mark Twain and Thomas Nast as literary and visual traditions of irreverent mayhem. It’s enlightening to think now how hilarious life could be when you have an artist a pen, an audience and a regular space to work their imagination. It’s more than a small pleasure as well to see how in Gurbo’s case the results could be so consistently rewarding. Filled with pictorial puns, rife with New Yawk smarts, and loaded with autobiographical traumas (like failed relationships and housing insecurities)„ Gurbo has an uncanny access to the subconscious. Every week for a dozen years he did what he could to raise people’s consciousness just a tiny bit at a time, and if that meant warping our consensus reality along the way, so be it. Here then is the strange evidence of a true peripheral visionary, or as Walter told us, “what you don’t see out of the corner of your eye.”

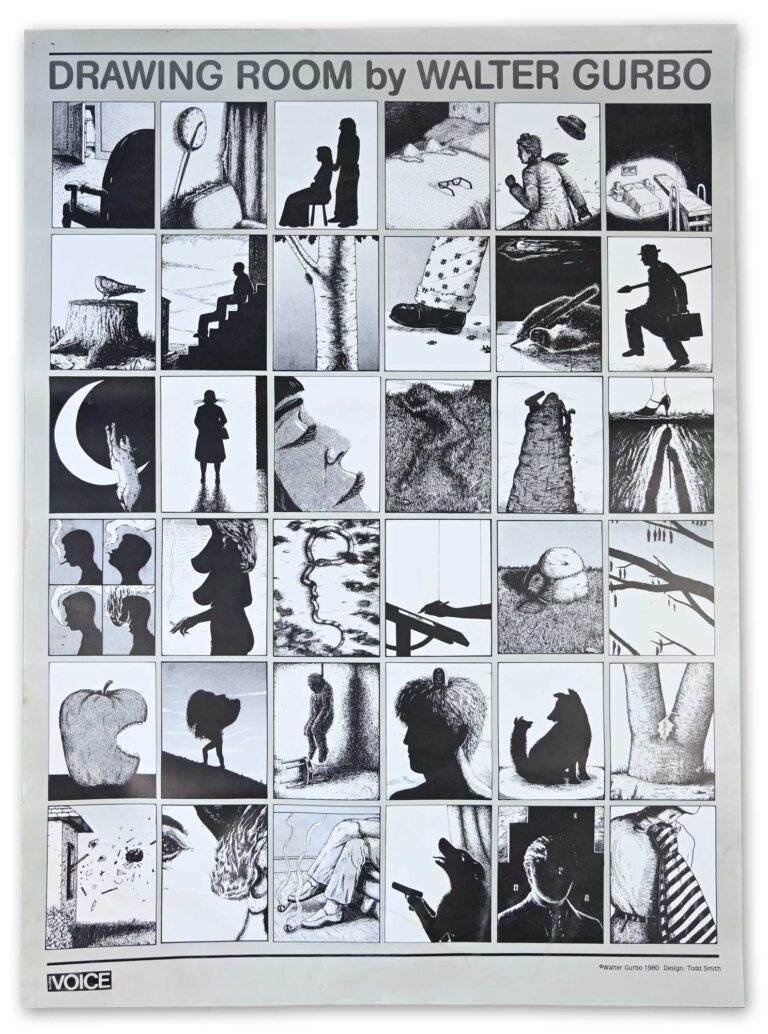

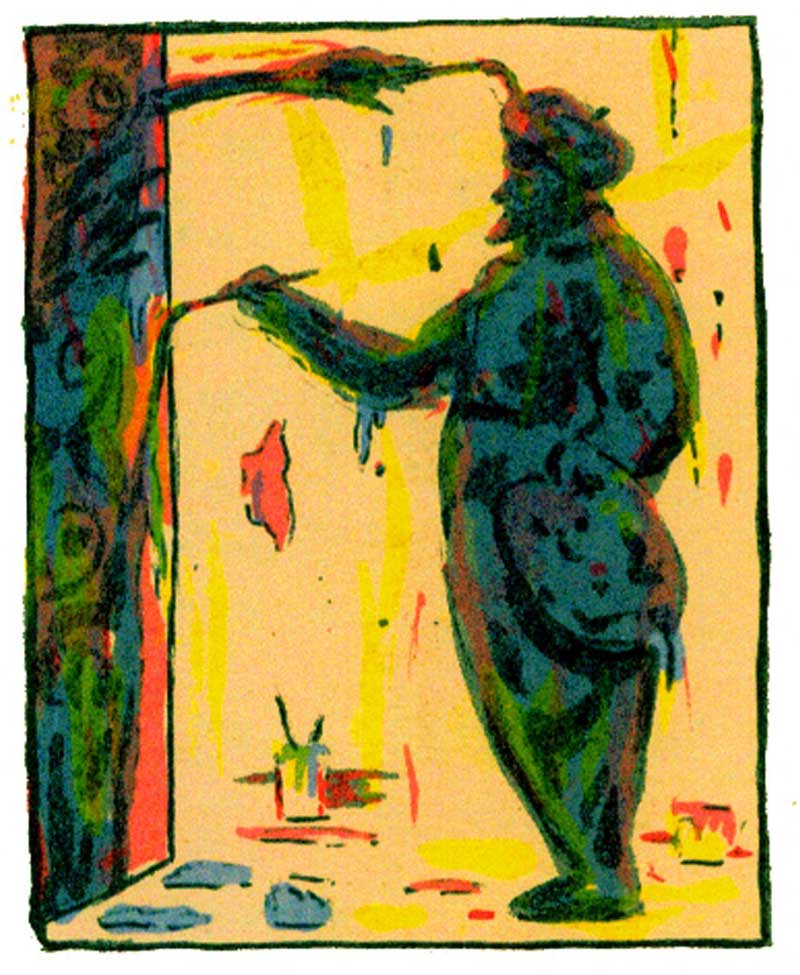

Vintage

DRAWING ROOM

POSTER

On Sale Soon!